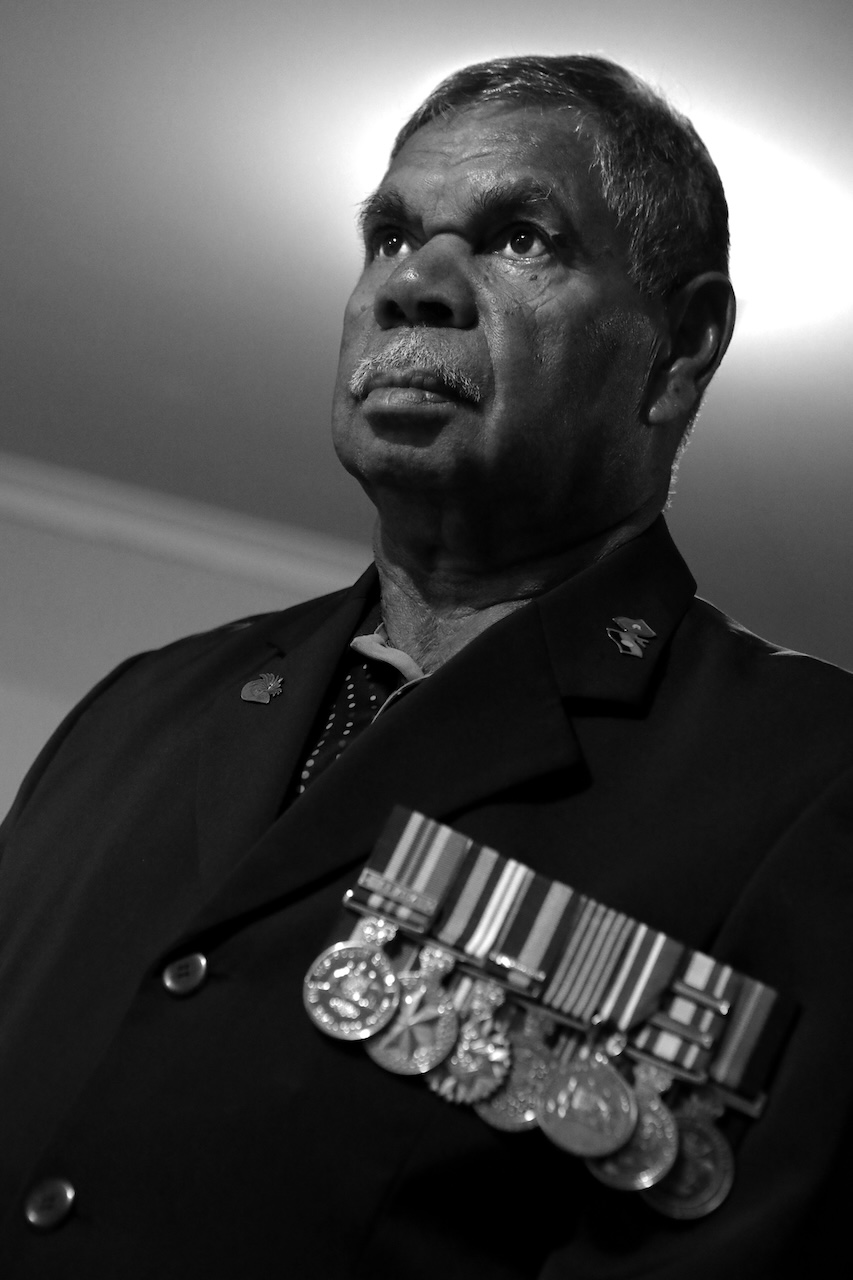

Harold Woody Humes

Noongar Wilman Man

Corporal

6th Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment

Royal Australian Infantry Corps

Australian Army

Senior Aboriginal Police Liaison Officer

Western Australia Police Force

Medals

Australian Service Medal with clasp SE Asia

National Police Service Medal

Defence Force Service Medal with 1st clasp

National Medal

Australian Defence Medal

WA Police Force Service Medal with 1st and 2nd clasps

WA Police Force Aboriginal Service Medal

We grew up in Wandering, a little country town, about 180 km from Perth. I was the youngest of 12 children. The government policy at the time was that Aboriginal people weren’t allowed to live in towns. We lived in a tent and a tin shack until I was nine when my father died. When I was 13, my mother drowned, and my brothers and sisters were taken away to Perth. I was left behind with my older brother. I left Wandering when I was 16 and went to stay with my brother Bill in Sydney. That was the first of many culture shocks. I arrived at peak hour just as a sea of white people poured out of the buildings like ants! I worked at a hardware store for a year and then enlisted in the Army in March 1971, when I was 17.

After training, I was posted to the infantry. I volunteered to go to Singapore with Delta Company 6th Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment (6 RAR). That was a culture shock too. I expected to see white faces like in Sydney, but the people were all Asian. In Singapore, we were part of the ANZUK Brigade with New Zealand and British troops. While we were there, I was transferred for 3 months to a parachute unit in England. Another culture shock – it was freezing in England! I took part in honour guards for her late Majesty, the Queen. We returned to Australia at the end of 1973, then in December 1974, Cyclone Tracy flattened Darwin and our battalion was deployed to help in the clean-up. Throughout my time in the army, I worked with many nationalities, Americans, PNG soldiers, and the Gurkhas. You learn something new wherever you go, working with different people and learning about their cultures.

I wanted to do something different after 20 years’ service so I left the army in May 1992. I joined the Western Australia Police Force and served there for 25 years. I enjoyed being in the police. I hadn’t come across racism while I was in the army, we were all mates. But in the police force, I found that a lot of our officers didn’t understand how hard it was for Aboriginal people. I’d say, ‘Be a blackfella in my shoes for a while and then you’ll understand what we’ve got to put up with.’ I’m still trying to educate them about our culture and our people.

I continue to do my bit for our people here in WA. I’ve been presented with four awards, for outstanding achievement. I go to schools all over the country and talk to the kids. I run a learner driver program so people get their licenses, to help them get jobs. I speak to them about Anzac Day and what it means. When I was going to school, Anzac was only ever about white soldiers. It’s so important that kids know about all the Indigenous soldiers who have served.

You can’t change what happened in the past, but you can make people aware of it and help them understand. It was terrible and it’s still happening today. I’m just happy that I’ve got a lovely family. Michelle and I have been married for 39 years. We’ve got four children and 13 grandchildren. We take the grandkids out bush. We camp, have a barbecue and teach them to know and understand Country. They come over and want me to polish their boots, ‘Real shiny, Pop, like in the Army.’ They ask me to tell them stories. I tell them the one about being in the jungle up in Malaya, guarding the F111 fighter planes at Butterworth Air Base. We’d slung hammocks to sleep in. Sometime in the night, my mate woke me. ‘Don’t move!’ he whispered. There was a strange smell near us. A big orangutan had climbed down from the trees and was rocking us both from side to side in our hammocks!

I’ve never regretted my time in the service; the army taught me so much. I love my old army mates. I mightn’t have spoken to them for years, but they still ring me up or leave a message, ask me how I’m doing. The hardest thing for me growing up was not having my parents. When I joined the army, the old sergeant had said, ‘I’m your mum now, your dad, brother, sister, whatever you want me to be, I’m it.’ And that’s the way I always looked at it. The army became my family.