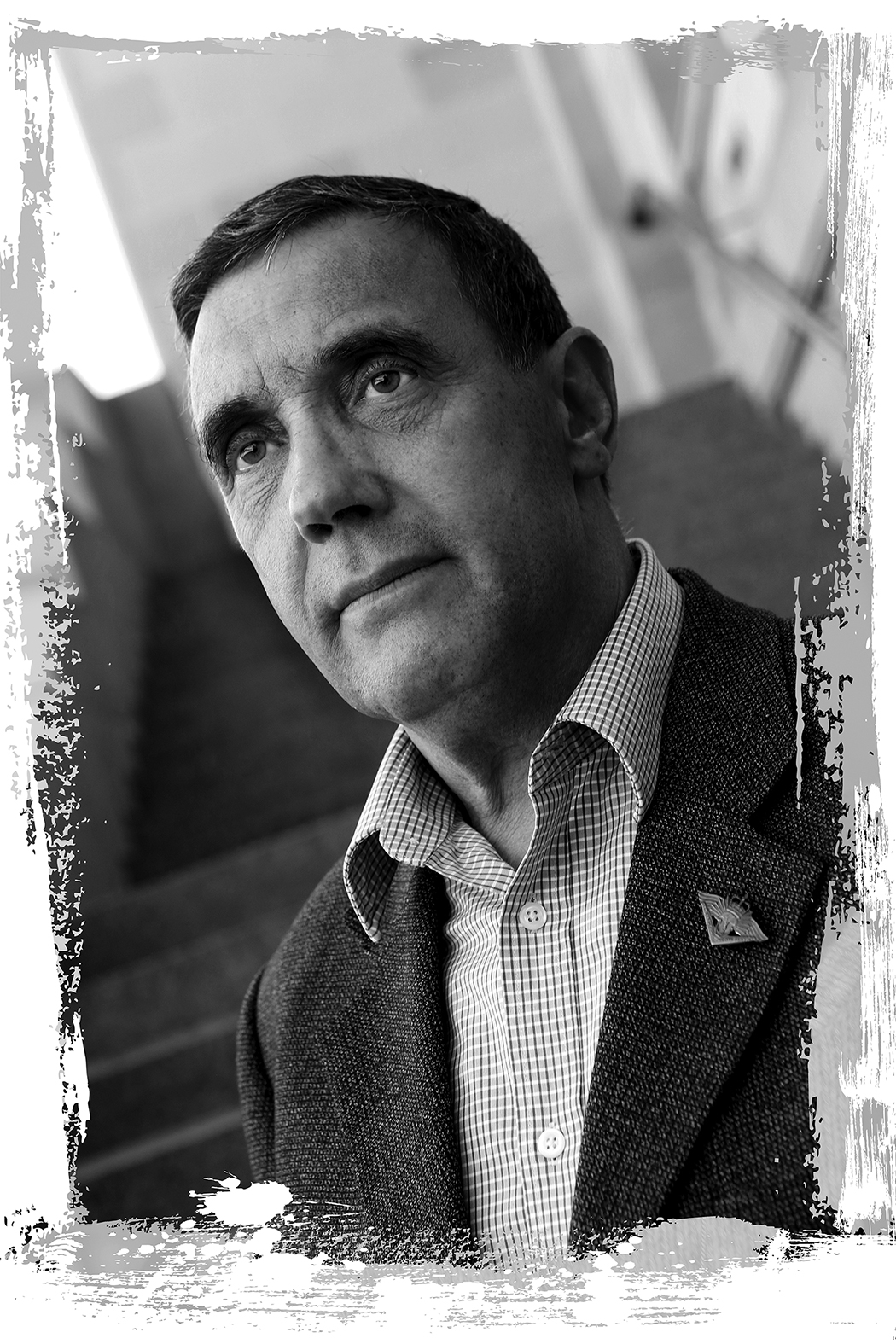

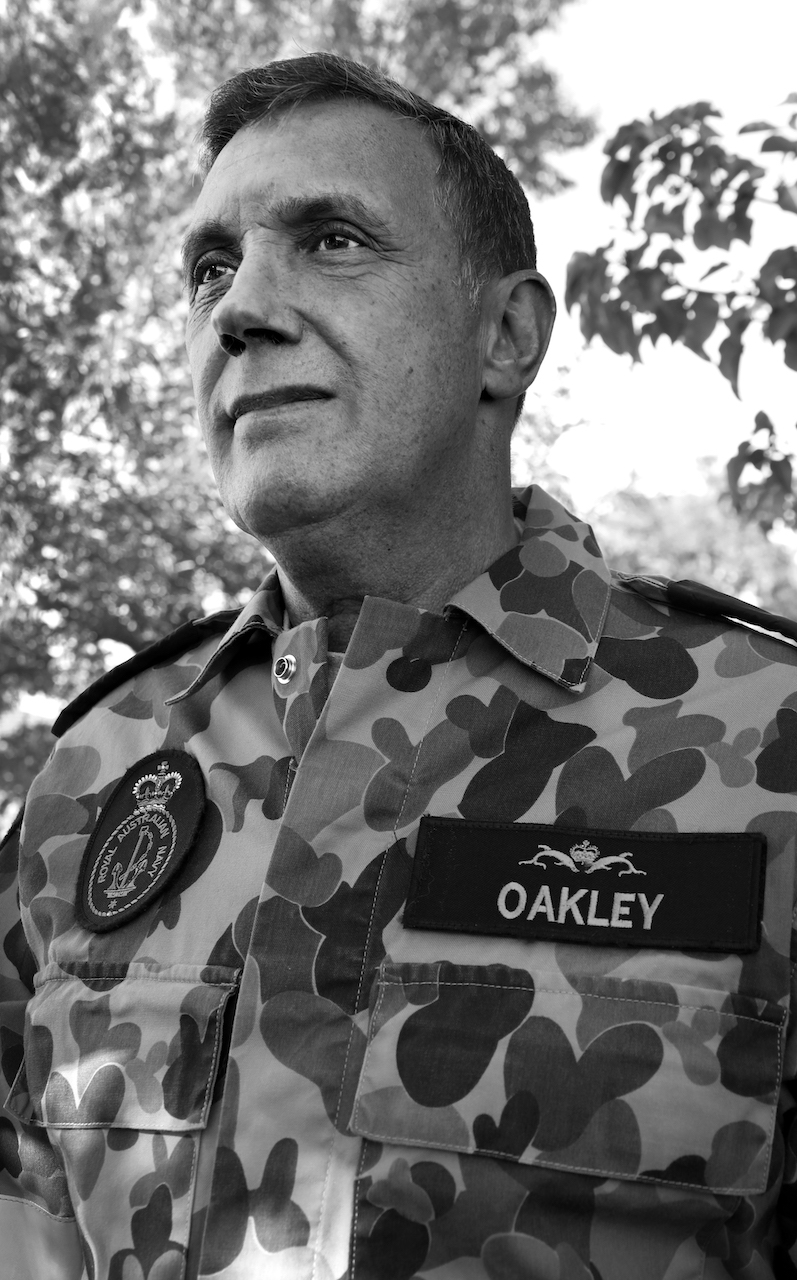

Gary Oakley OAM

Gundungurra Man

Squadron Leader

Royal Australian Air Force

Indigenous Curator/Historian and Indigenous Liaison Officer Air Force History and Heritage

Medals and Awards

Medal of the Order of Australia 2019

Australian Active Service Medal 1945-75 with clasp Vietnam

Vietnam Logistic and Support Medal

Australian Service Medal 1945-75 with clasp FESR

Defence Force Service Medal with 1st, 2nd and 3rd clasps`

Australian Defence Medal

Returned from Active Service Badge

RAN Submariners Qualification Badge

I grew up in Canowindra in Central New South Wales with my Indigenous father and non-Indigenous mother. My father had a council job running a treatment works. He had a position in society, and he worked for the council, and I could have got a council job too. But I was aspiring to something else. I wanted to travel, and I wanted to do things. So, I joined the Navy as a 15-year-old Junior Recruit. After your first year at HMAS Leeuwin, you’re supposed to get six months’ training on a ship to ground you in what the Navy’s about. Then you did your trade training, and then you got a posting to a ship’s company. My first posting was HMAS Duchess, but she was in refit, so they sent me to an apprentice training establishment, HMAS Nirimba, for a couple of months to wait for the Sydney to come back from Vietnam. I’d just turned 17 when they drafted me to the Sydney, an old, converted aircraft carrier, that went backwards and forwards taking troops and equipment to Vietnam. I think we took 3rd Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment (3 RAR) up and 7 RAR back, or 7 RAR up and 3 RAR back, I can’t remember.

We’d come in early in the morning before sunrise. You’d anchor and they’d put out the boat parties to circle the ship, dragging for swimmers and doing all that kind of stuff, and then you’d set up watchers around the ship to shoot at swimmers if they turned up. Funny thing was, the watchers were usually blokes like me, 17-year-olds, and they gave you a rifle and a magazine, but you weren’t allowed to put them together. You had to have the magazine in your pocket, and if you saw something going on, you had to ring up and ask if you could have a shot at it.

My job was on the seaplane crane. I was an ordinary Seaman Electrical Mechanic, and the offsider for the Leading Seaman. He drove the crane and I was the dogman unloading trucks and equipment or whatever. It could get a bit dangerous because you’d drive the vehicles onto a net and then lift the net and if they weren’t on properly and you’re underneath dogging, a truck could fall on you. Sometimes I’d get down onto the barge alongside and because you’re unloading stuff you’re talking to the Vietnamese people, and you’re talking to the soldiers who have been there for a while. You never stayed overnight in the harbour. They couldn’t control what was going on, they couldn’t see what was going on. If you hadn’t finished unloading, you had to pull up and go outside and then come back in the next morning. When you took a battalion up, you used to get milk in five-gallon tins, so you’d save the tins. And we would be on the quarter deck and the squaddies would be up on the flight deck and we’d be blowing up balloons and throwing them and the cans over the side so they could get a bit of shooting practice in. And there were always tug of war and running competitions with the Army on the flight deck at sea, and they had concerts in the hangar, and built a canvas swimming pool so the blokes could cool down. The ordinary seamen were moved out of the messes so that the soldiers could have them. We slept in one end of the hangar on hammocks hung from metal frames, and the only way you could get any fresh air or cooling air through was if they dropped one of the lift wells down. But then all the funnel smoke would get sucked through too.

When the soldiers were coming off the choppers, my job was to show them around the ship and get them used to stuff. When they arrived, the cafe would be ready to feed them, so you’d show them where the cafe was and line them all up and, and they’d ask why the sailors were standing back. And I’d say, ‘Because you’re our guests.’ But we knew that when the big café shutter went up, all the cockroaches would fall down. You had to flick them off your mash with a spoon. The Sydney was a cockroach palace. When the Army wasn’t on it, there were vacant messes with nothing in them, so the roaches lived in there. When you were unloading soldiers, you lined them up on the flight deck or inside the hanger and they would bring the Chinook helicopters in. One battalion would be unloading, and the other battalion would be getting in and going. Sydney had davits alongside for landing barges, and the Chinooks would take off and the wheels could get caught in the davits and these bloody great helicopters could come down on the flight deck.

If you ask me what I remember about Vietnam, it’s the funny, tropical smell, that hot tropical smell, and the smell of avgas (aviation gasoline). You’d look in the sky and there was a helicopter, and another one, and another one. There were choppers everywhere and the smell of avgas and the noise. I remember the heat, that funny smell, that wet dank sweaty smell, and avgas. Another thing I remember is, whenever we were bringing soldiers back, they’d come off the chopper and we would have these big tubs of lime drink with big chunks of ice floating in them and Anzac biscuits or rock cakes. They could have a big cold drink and a rock cake. The drink was really lemony, designed to stop scurvy. When we were working with the Vietnamese and the squaddies on the barges, we used to take them the lime drink too.

I liked my time as an ordinary seaman, as just a dog’s body. If you’re gonna have a battalion on the ship, you’re gonna have 800-plus people extra and you had to store the ship. Our job was to carry the big bags of potatoes and the drums of milk and the bloody beer issue, and all that. We were the slaves of the ship. And at six o’clock in the morning you had to get up. You couldn’t sleep in because you had to do compulsory PT, and you would do that on the flight deck even if there were waves washing over it. And surprisingly I liked that. The battalions were made up of full-timers and Nashos, but you couldn’t tell the difference. And that’s what I really liked about it. They were so well-trained you really couldn’t tell the difference. When we went in early in the morning to unload the soldiers it would go quiet; all these guys would be lining up ready to go into the helicopters and they would just go quiet. There was no talking. And they all got this look on their faces like, shit, where am I going? And you could actually see and smell the fear. And the guys coming out of the helicopters were all laughing and smiling and ‘yeeha’. These guys had been over there for 12 months, and they came back and they were not boys anymore. There was a look about them and a way they walked, and they talked, and how they looked after each other; the camaraderie and the love of each other. It was totally different. You really saw that change.

We didn’t do them any favours when they came back. They marched down the street and they had paint thrown at them. They weren’t allowed to wear uniform because people would call them baby killers. They joined the military, or they were conscripted to do a job that the government said they had to do, so why throw paint over them and spit at them? There’s a saying, ‘When they need you, they love soldiers; when they don’t need you, you’re the enemy.’ I noticed the change when they had the Welcome Home Parade in 1987. I marched in that, in the Navy section, and people came out and shook your hand and said, ‘I’m so sorry for what I did to you people. It wasn’t your fault.’ And I thought, well, it took you a long time and there’s a lot of people that you’re never gonna be able to say sorry to because they topped themselves or whatever. But it was a good thing that people came out and actually admitted that they were wrong. People have to realise, it’s a job and it’s a job where you could get killed but you do it because it’s your job and because of love of country. And that’s especially true with Indigenous people, we protect our country and our people. We don’t serve because we are war pigs, and we love to fight. We all serve, Indigenous and non-Indigenous, because we love this place enough to put ourselves on the line when we’re needed.

Up until 1949, Aboriginal people weren’t allowed to serve in the Australian Defence Force. In the First World War it was up to the medical officer to say; being black was a medical complaint because if you’re black you’re not smart. Some medical officers just saw another soldier, and some would say, ‘I really can’t let you join’. I know blokes who went to four different places or left the state to join under somebody else’s name to fight for country. It was the same for Vietnam, if you were called up for National Service and you’re Indigenous, you didn’t have to go. In the Defence Force you gotta trust the bloke behind you and you gotta trust the bloke in front of you, and it doesn’t matter what sexual preference, skin colour, or religion he’s got. If he’s got your back, you don’t have to like the bastard and he doesn’t have to like you.