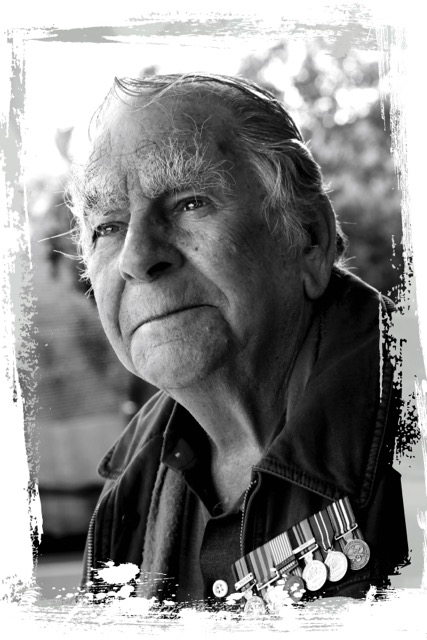

Norm Newlin

Worimi Man

Private

1st Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment

Royal Australian Infantry Corps

Australian Army

Korean War Veteran

Medals

Australian Active Service Medal 1945-75 with clasp Korea

Korea Medal

Australian Service Medal 1945-75 with clasp Korea

National Medal

Australian Defence Medal

Anniversary of National Service 1951-72 Medal

It was a stormy Wednesday morning in June of 1934 when I was born. Not breathing, I was blue and weighed about four pounds. A midwife dumped me in hot and cold water and got me breathing, then they wrapped me in a blanket with a hot brick and stuck me in the oven. I’ve been a survivor since day one.

I grew up in the only Aboriginal family in a small town in the Port Stephens area and was completely ostracised. People said things to my mother in the street when my young brother and I were with her, those memories will never go away. I got blamed for things being broken and stolen whether I did it or not and the copper used to walk into my mother’s kitchen and say, ‘Missus your kids’ve been pinchin’ again.’ He never called her Mrs. Newlin or showed her any respect. I hated school, was told I was stupid and not capable of learning ‘Get down the back, sit down and shut up.’ None of the local girls had anything to do with me and I never got into deep friendships with anyone. I didn’t worry, I was a bit of a loner and still am. I walked out of primary school when I was 14 and went to work in the bush. In 1951 I put my age up and went into the first intake of National Service in the Army where the discrimination continued.

I was posted to the infantry and sent to Korea. When people looked at movies and newsreel reports about the war, they didn’t know about the sight and smell of dead bodies that hung in the air with the smell of cordite and refugees fighting one another for scraps. I was young and blocked it out because if I didn’t, I’d go under.

I was drunk for a month when I came home. My mother was crook at me because she didn’t understand that drinking was the only way to block everything out and cope. Back then you were weak if you went to counselling, instead I was told to get over it and have a drink. I couldn’t sit down and talk to the blokes I went to school with, they’d never been in the army. I’d go to the pub with the blokes from World War I because they understood what I was going through. When I decided to stop drinking, it made a lot of difference psychologically. When I used to sleep, I’d wrap up in a fetal position and pull the blankets over me like a cocoon. As I sobered, I’d get further out of the blankets and now I’ve got my head and shoulders out. Traumatic stress exists, you can’t do and see all I did and not have had problems. I’d wonder if my head would explode if I didn’t compartmentalise it. Even after all these years, I get flashbacks.

I unloaded a lot in my writing. I didn’t want anybody to see what I wrote so I either burnt or flushed it down the toilet. When I first started to write, I didn’t realise I was writing out of anger, but you can’t go around hating people all your life. It doesn’t affect them, only you. One poem I wrote called ‘The Sanctimonious Bastard’ was about the things that happened to my mother. After I wrote that I sat down, looked at it and had a cry, then said that’s it I would never write another, but about six weeks later something said, write this. I wrote a poem called ‘Sweetwater’, it was a breakthrough. Then after walking around Uluru with my son, another came to me, and I called it ‘Eternal Life’. Having them published gave my heart a chance to heal.

I got my Bachelor of Communications, Honours from University of Technology (Sydney), an Associate Diploma in Adult Education and I am a Justice of the Peace. I have spent much of my life working and consulting in Aboriginal affairs and sittings on boards including the Campbelltown City Council Aboriginal Advisory Committee and I received the Campbelltown City Council Heritage Award.

Most of my mates are gone now, most of them were older than me because I put my age up. It’s sad when I look and see ’em how I knew ’em when they were nice and brightly. My brother was killed in World War II, he’ll never be more than 18 and I try to envisage him as being older. There were eight of us in the family, six boys and two girls. Now only my brother and me are left and he’s four years older than me. So yeah, I wonder how long I’ve got. But you can only live life a day at a time and enjoy life and try not to do any damage to anybody.