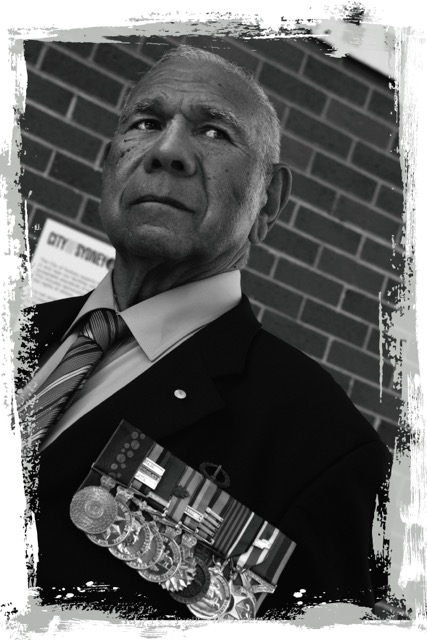

Roy Mundine OAM

Wehlubal People of the Bundjalung Nation

Warrant Officer Class One

5th Battalion Royal Australian Regiment

Royal Australian Infantry Corps

Vietnam War Veteran

Inaugural Indigenous Elder of the Australian Army

Medals and Awards

Medal of the Order of Australia (Military Division) (1987)

Australian Active Service Medal 1945-75 with clasps Malaya, Thai Malay and Vietnam

General Service Medal with clasp Malaya

Vietnam Medal with oakleaf (Mention In Dispatches)

Australian Service Medal 1945-75 with clasp SE Asia

Defence Force Service Medal with 1st, 2nd, 3rd and 4th clasps

National Medal 1981

Australian Defence Medal

Republic of Vietnam Campaign Medal

Pingat Jasa Malaysia

Infantry Combat Badge

I was born up in Northern New South Wales where my father worked for the main road department. In the 1950s, I joined the military. We trained and then shipped off to Vietnam. We came back home and we prepared for our second tour and got shipped off again in April 1969. We’d been up north, came back, regrouped, and went back out into the field towards Long Green, clearing areas, and we came across an enemy bunker system. I went to check it out, and that’s when I tripped a mine, which blew my leg off. Even though I was in considerable pain, I ordered my section to stay out of the area and directed them to new fire positions after I gave them full details of the enemy bunker system. For over 40 minutes, I continued to give instructions to my section and refused to allow any platoon members to move near me, until engineers had cleared a path through the minefield. Even in the chaos, I directed my team away for their safety until we cleared out the area, then I was helicoptered out to a hospital. That’s the military, constant training for moments like these.

If you’re leading the squad, and things go south, it’s on you. Your job isn’t just to fight; it’s to lead and organize. An NCO or officer shouldn’t be on the front lines; you’re no good dead. There are things they don’t tell you, but you learn them. Life in the service is tough, you make the best of it, and despite everything, there’s enjoyment to be found. The difference between military theory and the real thing is stark. In theory, no one dies. But in reality, you learn to live and work together in close quarters, learn from those who know the art of soldiering – the old soldiers from WWII and Korea. They may not have been academic, but they knew their craft. Today, it’s different; too much academia and not enough real soldiering. Infantry’s job is to engage in organised violence, a reality many don’t want to face. When it comes down to it, no matter how much education you have, it’s a harsh reality that people die and get badly injured. Veterans understand each other in a way civilians can’t. We come together, share stories that others wouldn’t grasp. Our leaders send others to war without understanding the reality. Back then, we looked after our own better than the system did. Even when you’re recovering, you have to interact with the world outside. Some folks have minor issues that turn into huge problems, and the sad truth is that suicides and self-harm are probably on the rise. There’s a lot of young people facing this. Education is important, yes, but it’s not just about getting a degree and sitting around writing papers. You’ve got to be out there in the community. In today’s world, if you just sit around feeling sorry for yourself, you won’t make it. You can’t just stay in one place; you need to travel, meet people, see the world. You’ll realize your problems aren’t as big as they seem. It’s dog eat dog, and no one has the time to hear about your problems; they’ve got plenty of their own.

When you serve, you place the needs and safety of others before your own. I received an OAM (Military) for my 36 years of service with distinction in the armed services. My old battalion, the 5th Battalion, honoured me by naming a military operation in Afghanistan ‘Operation Mundine’. We, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders, have served in virtually every conflict and peacekeeping mission from the Boer War to Afghanistan.